Martha had once been chief legal officer of Social Media Corp, a social networking leader. She’d worked side-by-side with the founders and been one of the ‘family.’ For five years she’d enabled the very behavior of which, today, she stood in court and accused them.

Martha had once been chief legal officer of Social Media Corp, a social networking leader. She’d worked side-by-side with the founders and been one of the ‘family.’ For five years she’d enabled the very behavior of which, today, she stood in court and accused them.

In an unequivocal voice she declared, “Just because they provide the pipeline through which user information is delivered does not entitle them to use that information, either directly or indirectly. Even though users check a disclaimer and acknowledge the company’s access to their personal data, they are still protected by the privacy laws of their country. The users of SM Corp can join for ‘free,’ but they nonetheless pay an unwitting — and illegal — cost.”

The defendants felt betrayed by their former colleague. They’d built a bright, progressive company that everyone wanted to work for. They were generous to employees and encouraged their creativity, letting them explore and sometimes fail. They provided a relaxed, high-tech workspace filled with wholesome, free food and beverages. They offered the best health coverage money could buy and a host of wellness options, including mindfulness training.

Which is where it all began.

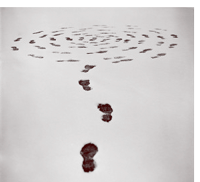

Mindfulness put her in touch not only with her stress

and reactivity but also with her ethical footprint through life

Martha loved her job. At any rate, she was excited about ‘creating new realities,’ as the slogan went. She enjoyed welcoming visitors into her bright office and talking confidently about the future. She loved being at the forefront of her generation, of working with the brightest minds around.

Still, the job was tricky. Getting people to sign up for a free account was one thing; Turning their aggregated data into a revenue stream — a legal one, that is — straddled a fine line.

Martha’s job was to make sure SM Corp didn’t cross it. In the early days, she was sometimes the only naysayer in a room of inspired engineers, ‘No, you can’t do that.’ She shocked them, but knew how to deliver the news. They respected her.

In return, she knew they weren’t greedy; they didn’t drive fancy cars or live ostentatiously. Out there on the leading edge things just got a little giddy, even electric. Sometimes she ended up just as frazzled as the front-line coders. That’s why she lobbied for the mindfulness class. She read in Time how all the big companies were using it to augment their employees’ health, creativity and productivity.

She took to it like a duck to water. It clarified her thinking and helped her center herself when she felt overwhelmed. She learned the power of silence, to watch what was going on without judgment and to shift the burden of communication from speaking to listening. Things began to change at home too, where she and her husband juggled intense professional lives with parenting their two children. She experienced moments of peace and clarity, and wanted more.

She took to it like a duck to water. It clarified her thinking and helped her center herself when she felt overwhelmed. She learned the power of silence, to watch what was going on without judgment and to shift the burden of communication from speaking to listening. Things began to change at home too, where she and her husband juggled intense professional lives with parenting their two children. She experienced moments of peace and clarity, and wanted more.

Martha wasn’t interested in religion, but she was intrigued to learn that this modern scientific practice was rooted in an ancient tradition. She signed up for an online Buddhism course and discovered that there was more — much more. Focused attention was just one element. Mindfulness helped her see into herself, but in all that raw data there were patterns to discern, and insights. From those emerged a desire to grow — but in what direction? This, Martha believed, was the essence of ethics.

Without even realizing it, she’d distanced herself one small stepat a time from what mattered to her more than anything else.

Ethics was why she’d become a lawyer in the first place — naively as it turned out; law wasn’t the same thing at all. But she’d invested in school, then in her career, and did what she had to do. There wasn’t much time to think. Without even realizing it, she’d distanced herself one small step at a time from what had once mattered to her more than anything else.

Her mindfulness practice put her back in touch with the thoughtful space in which those thoughts had originally germinated. She contemplated all the small steps, mulled over the compromises of the last five years and questioned her integrity.

Her mindfulness practice put her back in touch with the thoughtful space in which those thoughts had originally germinated. She contemplated all the small steps, mulled over the compromises of the last five years and questioned her integrity.

Which was what, exactly? Was it just behaving in ways that were acceptable to others? She always felt that was a cop-out. Where was the dignity in that? With her new clarity she saw that integrity meant to become complete in her own eyes. Mindfulness had put her in touch not only with her stress and reactivity but also with her ethical footprint through life. What mattered most was what she was passing on to her children, not through words and ideas but as a role-model, through her behavior.

Martha turned to her parents. They were proud of her success, but had never been as impressed by her employers as Martha. They’d raised her to make the world a better place, and considered social networking a step backward. Martha never argued with them — they were from another time after all — but one day she read in a book review that Google was, “in the business of distraction.”¹

Distraction wasn’t simply an unfortunate side-

effect of social networking. It was the point.

That stopped her in her tracks. She’d been noticing how automatically she reacted to the twitches of her smart phone; how often she turned to technology for momentary distraction; how her attention was increasingly fragmented. She also noticed that, for her colleagues, ‘good’ meant good engineering, and technical progress was precisely equivalent to social progress. It was as if humanity was heading for tech heaven, and they were the priests. Cults were usually fringe groups, but this was mainstream, addictive and, she furrowed her brow — destructive.

She was shocked by her insight. There’d be a price to pay, and she laughed uneasily at the irony. Mindfulness helped her colleagues focus on fragmenting their users’ attention. The more often a user clicked, the more money the company made. Distraction wasn’t simply an unfortunate side effect of social networking. It was the point.

The other side of that irony was that the simple pursuit of inner peace had turned Martha’s life inside out. Here she was in exactly the job she’d worked so hard for, only to find it unconscionable.

Cautiously, she probed colleagues in search of allies. She expected resistance but it was worse than that. They were insulted by her accusations.

“Accusation?” she protested. “I didn’t mean to….”

But the look in their eyes was unmistakable. She’d positioned herself beyond the pale. For them, the company was on the leading edge of a new wave. They were transforming the world, empowering people, creating wealth. What was not to like? Mindfulness was personally helpful and great PR, but it was there to support their work, not to challenge it.

Martha began to feel weirdly introverted, afraid she might be too wrapped up in herself, but the shift in her perception was irreversible. She couldn’t account for why mindfulness had pushed her and her co-meditators to such opposite poles, but she hadn’t felt this sure of herself since college. There was no doubt: mindfulness was growing her integrity; the job was compromising it.

Her parents were supportive; a little nervous for her future but proud to see Martha make sacrifices for what she believed in. They talked into the night about how things used to be. Through their eyes, Martha saw more clearly the challenges of the future. There was no reversing the technology, but the notion that society would be steered merely by what was technically possible was disturbing. To her colleagues, a new ethics, society, politics and economics would emerge naturally in the digital age, not the other way round. Something was wrong with a picture in which users were the product and the corporation owed them nothing.

Her parents were supportive; a little nervous for her future but proud to see Martha make sacrifices for what she believed in. They talked into the night about how things used to be. Through their eyes, Martha saw more clearly the challenges of the future. There was no reversing the technology, but the notion that society would be steered merely by what was technically possible was disturbing. To her colleagues, a new ethics, society, politics and economics would emerge naturally in the digital age, not the other way round. Something was wrong with a picture in which users were the product and the corporation owed them nothing.

Once her mind was made up, Martha’s resignation wasn’t the bitter pill she feared. She felt empowered, primed to follow her passion. As she reoriented herself in the following weeks, she came across this challenge from a neo-Buddhist blog site, and pasted it on her wall:

“Does your mindfulness practice penetrate deep into your subconscious to uproot narcissism, greed and confusion; or, does it leave you feeling serene and unquestioning? Is it a tool for unflinching self-discovery; or, is it a way to become the nice person you always wanted to be? Does it reveal life’s ultimate groundlessness; or, does it console you with imaginary certainties?”Martha joined an activist group that lobbied for digital privacy. Meanwhile, the corporation continued its mindfulness classes. On the whole, they made employees happy and boosted the bottom line. As far as they were concerned, Martha was just weird — an aberration.

Martha turned to the jury and showed, as only an insider could show, just how the corporation used its users, offering them a free service that actually cost them their privacy; providing information without cultivating intelligence, creating a hive mind rather than a community of the self-reliant, making people less contemplative, more easily overwhelmed and increasingly distracted.

“Distraction,” she raised her voice, “is their ultimate goal.”

The judge removed his glasses and locked eyes with Martha. She had his undivided attention.

=================================

¹ The Shallows, by Nicholas Carr

“If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.”

I don’t agree with this at all. Sounds like a typical fascism/police state phrase. I’m sure everyone has something they don’t want other people to know. It’s called privacy, and it’s a human right. In fact, this phrase is astonishingly stupid for someone in such a position.

Yep. We all thought Big Brother was going to be the state. Looks like it’s going to be the corporation.

They make “the beast of two backs”.

If I put two books before you, say a book of basic chemistry and the other a Calvin and Hobbes collection, is it my responsibility to steer you in your choice? If I’m your teacher, perhaps it is but otherwise?

I believe Martha missed this point. To be more accurate, It’s not that Google offers you two books, it’s that it offers you hundreds of thousands of books. The problem of distraction is more of sheer volume. One has to reflect if the material fits the needs, a task itself. Is that Google’s problem or one of our choices.

Hi John: So Google has no agenda?

Oh I’m quite sure Google has multiple agendas and first in line is turning a tidy profit. However I don’t fault Google for that as long as it remains careful to act ethically as a corporation. What is ethical as a corporation, that’s a tough question.

The problem with the corporation is that, although it’s incarnate with the flesh and blood of its employees, it is an inhuman, emotionless entity fixated on the bottom line. Its executives may be well-meaning, but while representing the corporation they have little opportunity to behave morally, which is how Eric Schmidt came to make that ridiculous statement. Government is supposed to intervene when necessary, but most states are now smaller than the corporations they host, and beholden to them. Perhaps this is the decadent phase of capitalism.

The “problem of distraction” is much wider than that, and yes Google is implicated at the very core of it. It’s not simply an issue of volume — which is not itself without draining effects on our attention — but also one of continually increasing, and unquestioned, fragmentation of our consciousness. There are many other examples in Nicholas Carr’s book which describe this angle. Jaron Lanier’s inside tech critique, “You are not a Gadget” is also a recent book which is an insightful commentary upon the social promise and hype of the web versus the reality.

I say accelerating “fragmentation” because the Google model (and Amazon’s, and so on…) derives it’s profit from allowing (and making possible) numerous third parties to push content in front of your eyes based upon targeted information which has been gathered about you. It proffers these visual interruptions (which also can be audial) in complete ignorance of the context already operating within your mind, your consciousness. Reading about conflicting theories of meditation and trying to concentrate? Time for a flashing message about that apple pie recipe you clicked on last month. It’s actually a school — if you even realize you’ve enrolled. How much distraction, and in how many forms, can you handle while still functioning with any depth or authenticity? Not overloaded yet? No problem, we have Google Glass on the horizon so we can further mess with your visual content.

It’s fun to have a corporate motto like ‘Do no Evil’. Would be more meaningful if there had been any real and scrutinizable effort to clarify what Evil means in the first place. Apparently it didn’t mean refusing to comply with NSA demands about making our data available — until of course the whole hullabaloo became public knowledge and there was suddenly the possibility of public outcry. But not surprising… who has time to reflect upon the subtleties of what Evil means in a social environment whose primary means of communication is bursts of 140-or-less character strings containing clickable links to further distractions?

“Distraction is their ultimate goal.”

Have you ever noticed the hordes of twenty-somethings with their “Stupid” phones in public places? No conversations, no interactions with the people around them, they fidget with their electronic gadgets like the electronics zombies that they are. A whole generation of distracted E-Zombies.

Of course this is what the corporations want. Noam Chomsky said all corporations are unaccountable private tyrannies. If you work for a corporation you’ll lose your freedom and ethics. What corporations replace your lost freedom and ethics with is addiction. Addiction to materialism or excess respect for authority. I learned this long before I meditated. Too bad Martha had to learn it the hard way.

Most people seem to be addicted to the merry go round. I bet if you were able to wrench an E-Zombie’s attention away from their gadget and asked them,

“Have you ever meditated or tried quiet contemplation?”

Their reply would be, “I think there’s an app for that!”

🙂

Fascinating story! Sounds like Martha found out that, while you might learn mindfulness to improve your productivity at work, you can’t actually BE mindful without confronting the whole of your life and looking straight at whatever comes up. I bet there will be many, many more Marthas arising out of the various wellness programs that are integrating mindfulness, at the office and elsewhere.

I hope so Mark, but I don’t expect so. The Marthas of this world have always been a tiny minority. However, they never go extinct. 🙂

Scary when the tool becomes the user and the user a tool. On this matters it seems to me that there are a lot of grays and shadows with blurred lines. but I like very much the phrase:

“Does your mindfulness practice penetrate deep into your subconscious to uproot narcissism, greed and confusion; or, does it leave you feeling serene and unquestioning? Is it a tool for unflinching self-discovery; or, is it a way to become the nice person you always wanted to be? Does it reveal life’s ultimate groundlessness; or, does it console you with imaginary certainties?”

It’s a good guide.

After reading this post only today, it seems to have hit me like a brick.

Lately, a phrase I’ve heard many times keeps running through my head, “If you want what you’ve always had, keep doing what you’ve always done.” Honestly, although on the surface I have what many others would consider to be ideal, it has come at a cost that at one time I would never have been willing to pay.

I’ve wrestled for many months on what to do and have been high-centered, paralyzed with the discomfort of knowing that if I act on what I want to do that friends and family alike will roll their eyes and whisper under their breath that I’ve somehow gone off the deep end.

So, maybe it’s time to go off the deep end. Not that my intention is to alienate my friends, family, and co-workers but rather finally take action where I know I must.

Thank your for this post and thanks to everyone in the discussion for helping bring a little clarity.

Good luck Steve. It’s not always easy to do what’s right, but in the long run it’s always easier than compromising yourself.