Jeanne, an old student of mine, approached me the other day about my upcoming Mindful Reflection workshop. “When does it start?” she asked. “It’s about letting go, isn’t it? I’ve got lots to let go of. So much disappointment.”

Jeanne, an old student of mine, approached me the other day about my upcoming Mindful Reflection workshop. “When does it start?” she asked. “It’s about letting go, isn’t it? I’ve got lots to let go of. So much disappointment.”

I love that I teach something practical, that helps people change. Not so long ago skeptics would have said, “Ah, but does it?” Today, criticism is muted. Thousands of scientific studies point to the effectiveness of ‘meditation.’

Still, exactly what that means is far from scientific. The word covers a broad range of practices from transcendental meditation (TM) to tantra. At base, it’s about being quiet and not giving in to distraction, at least outwardly. Beyond that, there are so many variations that you can never be sure two people are talking about the same thing. There’s walking meditation and sitting, vipassana and mantrayana, and then there are things like tai-chi, yoga and Zen archery. Are these all real forms of meditation?

You don’t want to open that can of worms.

Mindfulness: It’s all about change

The meditation that Jeanne learned in my workshops is mindfulness. It’s all over the news these days for its effectiveness in fighting depression, managing pain, reducing blood pressure, treating psoriasis and a host of other conditions. Everyone’s heard of it by now. It’s not just for navel-gazers any more.

Like ‘meditation,’ the word ‘mindfulness’ too triggers a broad spectrum of thinking. Not everyone’s on the same page. At one extreme, it’s a religious practice, just one component of a disciplined, faith-based lifestyle. At the other it’s a non-pharmaceutical approach to stress.

I’ve travelled the gamut from religion to secularism, learning something at every step of the way and adjusting not just my conception of who I am but also how I feel about being me. I would once have described this process as mystical; today I’d call it practical, but I’d also shrug. Call it what you want; it’s a way of life, not a theory.

Mindfulness is not so much

about finding truth as being truthful

It’s all about change. Religious Buddhists want to change into enlightened beings. Secular practitioners want to change their emotional reactivity, or at least their blood pressure. The main complaint of religious types isn’t that secularists have it wrong, but that they’ve watered down a beautiful tradition so much that it’s lost all taste. In return, secularists point out that Buddhist beliefs in reincarnation and magical stories dilute the immensely practicality of mindfulness and turn off many who could otherwise benefit.

Does the truth lie somewhere in between? That’s an interesting question. Mindfulness is not so much about finding truth as being truthful. There’s a difference. The close examination of your own experience is highly subjective. The mind spins truth depending on what it wants from a particular situation. For example, when your ego feels threatened and really needs to win an argument, integrity might take a teeny-weeny back seat; only temporarily; with just a little white lie.

See what I mean? The first casualty of mindfulness is the notion that we’re lucid, consistent and in control. Take note of that as it happens, and you begin the process of rewiring of the brain that scientists get so excited about. Of course, repeatedly shooting ducks and painting sunflowers also rewires your brain, so that’s hardly the point.

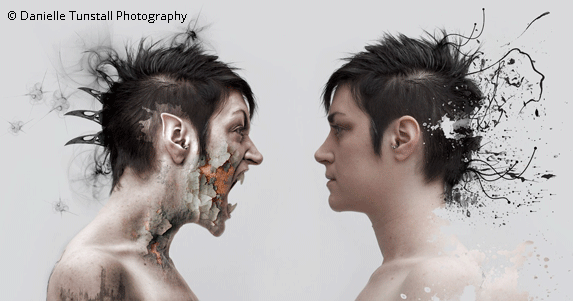

Jeanne learned to watch her disappointment and anger: how the emotions came and went, what triggered them and the chain of mental events they set in motion. She also learned that noticing them in real time — as they actually occurred in her daily life — gave her an opportunity to step back, not in one giant leap but incrementally. With practice and encouragement, she’s cultivating a counter-habit.

The way you describe yourself to yourself is

the arbiter of your happiness and unhappiness

Firming up this habit begins with the sort of practice that usually begins in a meditation setting. There, you learn to focus and to let go of distraction in ways that often lead to misunderstanding. Sitting quietly triggers boredom, and the inner chatter we’re trying to relinquish suddenly looks very tempting. To keep your attention in the present moment, teachers use expressions like ‘empty your mind,’ and ‘let go of your thoughts.’ Beginners often conclude from this that discursive thinking is a bad thing, which it isn’t; it’s just an obstacle to that particular practice. In other circumstances we need it very much, to think and function, to manage our careers and lives — and to reflect on our mindfulness practice.

As the mindfulness habit takes root, you also accumulate data about your experience — stuff to think about. We naturally process that data, just as I’m doing here. The way you describe yourself to yourself changes, and you learn that that description is the arbiter of your happiness and unhappiness.

For this reason I teach not just mindfulness, but mindful reflection, the practice of mindfulness in the context of a challenging, thoughtful life. It’s my middle way between the religious idea of transcending our human limitations and the coldness of a mere technique to calm you down. It’s not about transforming or curtailing your life, it’s about facing it creatively. What changes is your approach.

Jeanne knows that this is a lifetime’s work. There’s no perfection, no end-point. She works continuously to keep her baggage to a minimum and to be fully awake to all experience. She wants to sit in on more workshops because mindful reflection is not just about acquiring information but about digging deeper and looking at things from continually evolving angles.

Every day brings new challenges. It’s good to see the practice through the eyes of an experienced teacher. It’s made easier in the company of like-minded people. It’s something that happens in the privacy of your own mind, and yet it transforms your relationships to yourself and to everyone else. Above all, connecting is what life is all about.

The title of this post may sound like a pretentious philosophical treatise, and you may think, ‘Oh just get on with it!’ but this is not theory. It’s a niggling incertitude that drives me through each and every day. I know I’m not alone. After sifting though the suggestions and requests from our recent call to readers for feedback, I saw that I write this blog — and you read it — with a common purpose: we’re all trying to respond to this inner drive ‘to be’ with more reflection, less automaticity.

The title of this post may sound like a pretentious philosophical treatise, and you may think, ‘Oh just get on with it!’ but this is not theory. It’s a niggling incertitude that drives me through each and every day. I know I’m not alone. After sifting though the suggestions and requests from our recent call to readers for feedback, I saw that I write this blog — and you read it — with a common purpose: we’re all trying to respond to this inner drive ‘to be’ with more reflection, less automaticity.

I’ve been asked how mindfulness has worked out for me. Here’s a synopsis.

I’ve been asked how mindfulness has worked out for me. Here’s a synopsis.

Do you consider yourself a rational person? Your intelligence gives you an edge when it comes to some decisions, but what about emotional decision-making? What about automaticity?

Do you consider yourself a rational person? Your intelligence gives you an edge when it comes to some decisions, but what about emotional decision-making? What about automaticity?

I began teaching a new mindfulness workshop this week. As I took my place at the head of the large room I gazed with satisfaction over a sea of expectant faces and felt a nagging question form in the back of my mind. Is satisfaction an appropriate attitude? Isn’t that a bit like unseemly pride? Am I not supposed to be motivated by pure altruism? Even if I were—which I’m not—how could I even make such a claim?

I began teaching a new mindfulness workshop this week. As I took my place at the head of the large room I gazed with satisfaction over a sea of expectant faces and felt a nagging question form in the back of my mind. Is satisfaction an appropriate attitude? Isn’t that a bit like unseemly pride? Am I not supposed to be motivated by pure altruism? Even if I were—which I’m not—how could I even make such a claim?