Over the years I’ve taught hundreds of people the basics of mindfulness and Buddhist reflection. Many come back again. I take as a sign that I’m doing my job right, but I also know they’re taking responsibility for themselves. You have to work at opening your mind; it doesn’t happen by itself, and it’s not magic.

Over the years I’ve taught hundreds of people the basics of mindfulness and Buddhist reflection. Many come back again. I take as a sign that I’m doing my job right, but I also know they’re taking responsibility for themselves. You have to work at opening your mind; it doesn’t happen by itself, and it’s not magic.

Sometimes people express great interest in my workshops, but never show up; others come once but never again. I don’t take it personally. Mindfulness meditation takes some getting used to. Almost as soon as you sit down, you experience the urge to get up and make a snack, talk to a friend or watch TV. The practice is all about being still, watching your impulses rather than giving into them. That stillness eventually turns into a state of intense peace and clarity, but along the way there’s tons of resistance.

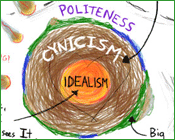

If you persist, the resistance becomes more strategic. You begin to value silence, but make exceptions: ‘spiritual’ conversations, speculation about past or future lives, explaining tragedies as part of a cosmic pattern, attributing causality to transcendant forces — these are all distractions from the honest task of insight.

If you really want to open your mind, there’s no room for magical thinking or spiritual speculation. Taking comfort in supernatural forces, amazing prophesies, tales of rebirth, almanacs, astrology, palmistry or tarot may make you think you’re living life differently from the masses, but you’re not; you’re just dressing up the same old escape patterns in fancy clothes.

The Buddha called his path, ‘the end to views.’ It’s a phrase to sit with; it encapsulates everything that mindfulness is about; paying attention to what’s actually happening here and now. The object is to be fully present to your life, not just to smell the roses, but to watch them decay as well. Mindfulness is not just a way to feel good, but to feel everything. Nor is it an end in itself. Without speculation, distraction, excuses and avoidance, you begin see your mind at work in real time. You become acquainted with your own motivations in ways that can be shocking. You may find you don’t know yourself all that well, and probably never will. That’s not a bad thing; the fact is, you’re changing and growing up as continuously as you did as a child.

We tend to embed ourselves in familiar patterns; they seem secure. We do the same things, react the same way and lean on habit. However, any safety you find in that sort of evasion is illusory; it limits your potential and restrains your perceptions. By not sticking your neck out, you miss what’s going on. The survival mechanism is an automatic response to life that turns instinctively to avoidance and denial. It can be a life-saver that enables you to function under short-term duress, but in the long term it ignores the great potential of human life.

Mindfulness pushes against the narrow confines of automaticity by clearing away speculation and habit, by bringing your attention to bear on the present moment and by revealing it to be constantly changing. It’s always unpredictable; it’s often astonishing.

However, it seems easier to dwell in thought than to be exposed to experience. Thoughts have their own momentum; they’re fluid and rarely hold you to account; they pull you away from what’s happening right now before your very eyes; they lull you with narratives from the past. Mindfulness, on the other hand, demands your full attention and hones your mental faculties. It teaches you that you haven’t finished becoming you; that life still holds surprises. Mindfulness makes you adaptable and intelligent in ways you’d forgotten. You see into your hidden recesses; you rediscover your resilience, adaptability and the greatest human strength of all: to reach out with uncontrived friendship.

Mindfulness is not a religion, a philosophy or a belief system. It’s a practice, based on the most fundamental act of consciousness: attention. Still, it’s not for everyone; you have to really want to explore yourself … as if you were a stranger, full of promise and wonder, with gifts for the world.

========================================================================

Stephen will speak at Hudson’s Awakening Festival, June 18th: www.awakeningfestival.org.