I don’t know what to do with my disappointment. It took me years to accept that Buddhism was not just profound scripture but also an infernal institution. Today, mindfulness has been hijacked by The Corporation, distilled into twenty-first century opium. Where’s a modern-day subversive supposed to lay his head?

I don’t know what to do with my disappointment. It took me years to accept that Buddhism was not just profound scripture but also an infernal institution. Today, mindfulness has been hijacked by The Corporation, distilled into twenty-first century opium. Where’s a modern-day subversive supposed to lay his head?

Why subversive? Think about it: the Buddha declared everything contingent, unsatisfactory, selfless — and chose homelessness over a life of power and influence. He abandoned his wife and son. He spent the rest of his life begging on the streets. Literally. Even after fulfilling his quest, he stayed away from civilization.

Today, who follows the Buddha into homelessness? Even venerable Asian monks live in nice monasteries. Meanwhile, mindfulness is settling very comfortably into the Googleplex and elsewhere where, as the BBC says, ‘it’s highly beneficial to both businesses and their employees.’

Funny, I thought the point of mindfulness was to see the futility of gain and fame. Evgeny Morozov’s right when he says that CEOs are on a mission to ‘finally reconcile spirituality and capitalism.’ Have your cake. Eat it too. Lovely.

I thought Morozov made his point rather well, but instead of being attacked by rabid capitalists, it was the Buddhists who got upset. He committed the sin of discussing mindfulness as if it were a new fad, not an ancient spiritual practice. God forbid.

Joshua Eaton writes about ‘Gentrifying the dharma: How the 1 percent is hijacking mindfulness.’ Professors Ron Purser and David Forbes protest that ‘Google Misses a Lesson in Wisdom 101.’ When the founders of Google and Facebook recently joined Russian venture capitalist Yuri Milner to award prizes for life extension research, British philosopher John Gray asked, ‘Are Sergey Brin And Mark Zuckerberg God-Builders?’

Then there are the activists. Amanda Ream disrupted the Wisdom 2.0 conference while claiming that it presents, ‘evolution in consciousness of the wealthiest among us as the antidote to suffering rather than the redistribution of wealth and power.’ Sounds like communism to me, but that’s okay; the Dalai Lama’s a self-declared communist and he’s always being fêted at the White House, by democrats and republicans. They don’t take him too seriously.

What exactly is going on?

I’d say, same old. The nineteenth century captains of industry weren’t shy about co-opting the message of Jesus Christ. The Protestant Ethic turned out to be the twentieth century’s dominant ethic. We need our myths too, and what with the decline of religion and the ascent of scientism, the great myth of our time seems to be that we’ve finally broken free of myths.

We’re a passionate, crazed species. What other explanation is

there for continued optimism in the face of our deadly insight?

How anyone can fall for that one I have no idea. If we have no more mythic drives, why do we spend our lives chasing dreams of capitalism and communism, Buddhism and atheism? How come Hollywood’s still in business? We’re human beings. Myth is what we do. Ecclesiastes nailed it two and a half millennia ago, “…vanity of vanities! All is vanity.”

Mindfulness is not like that, we’re told. It’s ‘being in the present moment,’ no illusions, no judgment, no mental wandering, no disturbance. Full frontal focus.

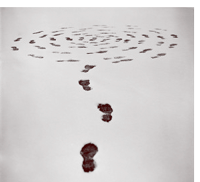

The way to sell snake oil is to tell people exactly what they want to hear, and I’m disappointed because I practice mindfulness and I teach it, but Morozov’s right: it’s become a fad. Real-world mindfulness reveals that mental stillness, total concentration and stress-free living are fantasies of desperate longing. Mindfulness may involve acceptance of what we can’t change, but it also impels us to engage with what we can. It clarifies our minds, but reveals our demons.

I don’t so much believe that mindfulness should be subversive, revolutionary or seditious. It’s more something I feel. The Middle Way is no wishy-washy compromise; it’s a dangerous tight-rope walk over the abyss of what Giacomo Leopardi calls ‘the emptiness of all things.’ We’re all going to die — remember? All that keeps us on our feet is the irrepressible delight we’re biologically programmed to take in our illusions.

To take those illusions as real dooms us, but without them we’re doomed too. Philosophers have found no satisfactory answer to the question of life’s purpose. Observe human behavior though: our intent is clearly to love and be loved. Hell, that’s even why we go to war. We’re a passionate, crazed species. What other explanation is there for continued optimism in the face of our deadly insight?

We’re on the verge of being too clever. Industrialization has gone digital. Efficiency’s measured in megahertz. Anomie is exponential. We live in times of epic change. All we can foresee is faster change. Are we about to outgrow the illusion that change equals progress, or will it soon be so taken for granted that we forget to question it? Decadence is just around the corner.

If this leaves you at a complete loss, go read Ecclesiastes. It’s only eight pages in my 1870 Spottiswood edition. Don’t be shy: they’re idiots who say you have to believe in a personal creator God to read the bible. This is a creation of the sublime human mind. It reaches through the ages. It grips you like a lover.

Buddhism has lost control of the term ‘mindfulness’

You’ll just have to do with mindfulness what you can. Buddhism has lost control of the term. It drifts through the idiom like a lost balloon, as misunderstood now as Karma™ and Samsara™. Some people will use it to calm down, perhaps even delay heart-attacks. Good for them. Soldiers will use it to steady their aim and be better snipers. It seems perverse, but how did snipers ever become good at what they do, whether or not there was a name for it?

Some of us will still use mindfulness to peer mercilessly into our own delusions. You might say that’s what it’s meant for, but that’s just your opinion. Funny, I used to feel like a deviant when I first came to Buddhism. I feel that way again, now as I distance myself from it.

Most people have no time for this nonsense. They want to get on with their lives. They’ll vigorously deny that living life to the full means questioning everything. Just as everything didn’t change with the arrival of Buddhism, everything’s not lost with its corruption. Life will go on, chaotic as ever, and just as we’ve done since we climbed down from the trees, we’ll continue to believe we’re on the verge of greatness.

Yes, go read Ecclesiastes.

“I was in a state of heightened slow motion, sensible to every movement of my body and to the roar of every in-breath and out-breath. I approached the bus stop, acutely alive to the universe of my own body and mind. The sounds of the jungle, wind in the high palms and the crunching of the dust beneath my feet overwhelmed my senses. In this moment of excruciating clarity, I stood outside the monastery gates awaiting the Colombo bus. From the bowels of the earth I felt a vibration that grew into a diesel roar and the screeching halt of the great vehicle in a cloud of dust. I placed one foot on the lower step, transferred my weight, slowly lifted the second and grasped the handrail. With a good-humored sigh, the driver let me climb aboard before pulling away as fast as the ancient motor would allow. I lurched from side to side, trying to follow the movement of my center of gravity, until a sudden swerve threw me conveniently into an empty seat. In the moment before I dropped my head in contemplation I noticed that everybody on the bus was talking, twitching, scratching and getting on and off at extraordinary speed. The passing countryside was a blur.” [

“I was in a state of heightened slow motion, sensible to every movement of my body and to the roar of every in-breath and out-breath. I approached the bus stop, acutely alive to the universe of my own body and mind. The sounds of the jungle, wind in the high palms and the crunching of the dust beneath my feet overwhelmed my senses. In this moment of excruciating clarity, I stood outside the monastery gates awaiting the Colombo bus. From the bowels of the earth I felt a vibration that grew into a diesel roar and the screeching halt of the great vehicle in a cloud of dust. I placed one foot on the lower step, transferred my weight, slowly lifted the second and grasped the handrail. With a good-humored sigh, the driver let me climb aboard before pulling away as fast as the ancient motor would allow. I lurched from side to side, trying to follow the movement of my center of gravity, until a sudden swerve threw me conveniently into an empty seat. In the moment before I dropped my head in contemplation I noticed that everybody on the bus was talking, twitching, scratching and getting on and off at extraordinary speed. The passing countryside was a blur.” [

The word ‘fundament’ means base or foundation, so you’d expect religious fundamentalism to be rooted deep in history, but it’s not. It started in the Southern United States after the First World War, a reaction to modernity’s brazen questioning of Christian authority. The Bible, ambiguous, contradictory, sometimes just plain indecipherable, was abruptly declared to be ‘literally true.’

The word ‘fundament’ means base or foundation, so you’d expect religious fundamentalism to be rooted deep in history, but it’s not. It started in the Southern United States after the First World War, a reaction to modernity’s brazen questioning of Christian authority. The Bible, ambiguous, contradictory, sometimes just plain indecipherable, was abruptly declared to be ‘literally true.’ Such feelings are fundamental in the literal sense; they never really go away.

Such feelings are fundamental in the literal sense; they never really go away.

We all need to belong. We also need to be self-reliant. When the two seem irreconcilable we try to think logically, but life’s not logical. You can figure out why you feel lonely but it won’t make you feel better.

We all need to belong. We also need to be self-reliant. When the two seem irreconcilable we try to think logically, but life’s not logical. You can figure out why you feel lonely but it won’t make you feel better. sometimes need “to just be.”

sometimes need “to just be.”

Martha had once been chief legal officer of Social Media Corp, a social networking leader. She’d worked side-by-side with the founders and been one of the ‘family.’ For five years she’d enabled the very behavior of which, today, she stood in court and accused them.

Martha had once been chief legal officer of Social Media Corp, a social networking leader. She’d worked side-by-side with the founders and been one of the ‘family.’ For five years she’d enabled the very behavior of which, today, she stood in court and accused them. She took to it like a duck to water. It clarified her thinking and helped her center herself when she felt overwhelmed. She learned the power of silence, to watch what was going on without judgment and to shift the burden of communication from speaking to listening. Things began to change at home too, where she and her husband juggled intense professional lives with parenting their two children. She experienced moments of peace and clarity, and wanted more.

She took to it like a duck to water. It clarified her thinking and helped her center herself when she felt overwhelmed. She learned the power of silence, to watch what was going on without judgment and to shift the burden of communication from speaking to listening. Things began to change at home too, where she and her husband juggled intense professional lives with parenting their two children. She experienced moments of peace and clarity, and wanted more. Her mindfulness practice put her back in touch with the thoughtful space in which those thoughts had originally germinated. She contemplated all the small steps, mulled over the compromises of the last five years and questioned her integrity.

Her mindfulness practice put her back in touch with the thoughtful space in which those thoughts had originally germinated. She contemplated all the small steps, mulled over the compromises of the last five years and questioned her integrity. Her parents were supportive; a little nervous for her future but proud to see Martha make sacrifices for what she believed in. They talked into the night about how things used to be. Through their eyes, Martha saw more clearly the challenges of the future. There was no reversing the technology, but the notion that society would be steered merely by what was technically possible was disturbing. To her colleagues, a new ethics, society, politics and economics would emerge naturally in the digital age, not the other way round. Something was wrong with a picture in which users were the product and the corporation owed them nothing.

Her parents were supportive; a little nervous for her future but proud to see Martha make sacrifices for what she believed in. They talked into the night about how things used to be. Through their eyes, Martha saw more clearly the challenges of the future. There was no reversing the technology, but the notion that society would be steered merely by what was technically possible was disturbing. To her colleagues, a new ethics, society, politics and economics would emerge naturally in the digital age, not the other way round. Something was wrong with a picture in which users were the product and the corporation owed them nothing.